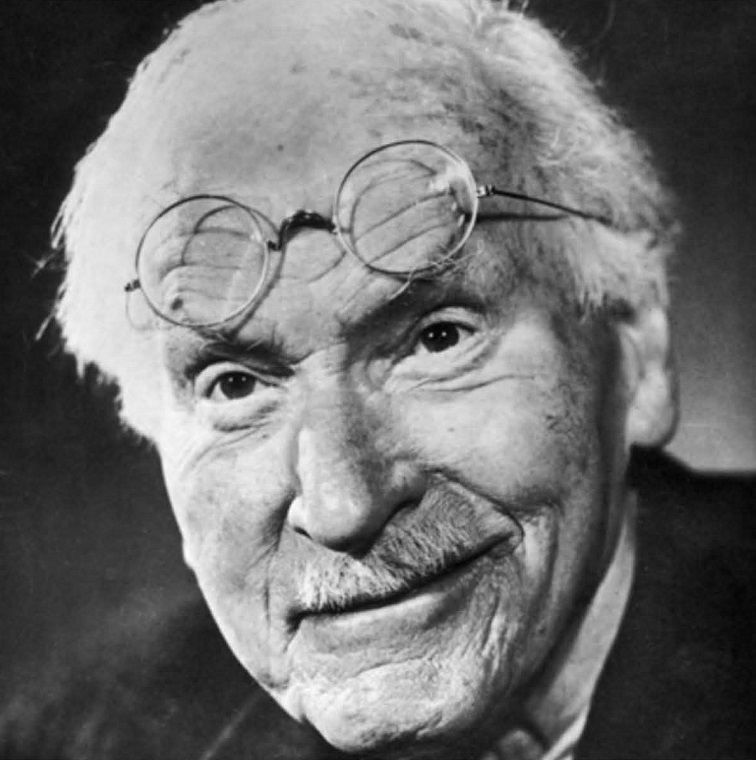

WHO IS C. G. JUNG?

C. G. (Carl Gustav) Jung, the first person to propose the existence of a collective unconscious shared by all people, was born in 1875 near Lake Constance in the north of Switzerland. While Sigmund Freud, an Austrian neurologist, is credited as the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst, it is Jung who ultimately brought to light how innately different individual humans are and how we must respect these differences. He emphasized the value of an individual to know oneself more and more, allowing one to become as much of one’s unique self as possible. Referred to by Jung as “individuation,” this is the process of active engagement with the movement toward wholeness. He taught that this discovery through self-reflection could continue over one’s lifetime. Jung himself demonstrated this; in his many writings he sometimes revisited and questioned his own earlier ideas, and on occasion, he apologized to individuals that he had hurt or offended in his writings.

As a solitary child, Jung’s outdoor play influenced his lifelong love and respect for the natural world. In 1895, at 20 years old, Jung entered medical studies at the University of Basel. Through specialization in psychiatry, he pursued his twin passions of biology and the humanities.

His career as a psychiatrist began at Burgholzli Psychiatric Hospital in Zurich. Here he conducted research in word association, which contributed to his uncovering of emotional complexes, a central theoretical aspect in his later thinking.

In 1907, Jung met Sigmund Freud and the two developed a close relationship. Ultimately, their differing views led to a break, and in 1913 the two men parted, each to further develop his own psychological methods and ideas. The relationship rupture thrust Jung into a period of self-exploration, which he documented and illustrated in the Red Book, a large volume published in 2009. This pursuit informed the development of his theories of the archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation, ideas that form the foundational nucleus of Analytical Psychology. His 1921 book, Psychological Types, presented Jung’s research on personality differences out of which he developed his ideas of personality typology, including introversion and extraversion.

Jung married Emma Rauschenbach in 1903; together they had five children. His personal courage and limitless curiosity propelled a lifetime’s work of research, writing, travel, and clinical practice. Jung died in 1961 and is respected as one of the brilliant minds of 20th century psychology. His work and thinking have impacted many fields including philosophy, anthropology, ecopsychology, theology, and most of the arts. Today, his ideas continue to be expanded, refreshed, and built upon by a diverse array of international scholars and clinicians.

WHY IS JUNG’S WORK RELEVANT NOW?

Jungian-informed thinking proposes that the vast nature of the human psyche is as rich and expansive as the outer universe. Jung taught that we can explore, understand, and make use of increased realms of consciousness. When we are strengthened with knowledge of ourselves as individuals we may have greater capacity to bring the vibrancy of increased consciousness to bear on the problems that push against humanity. Focused attention on inner life can help us bridge the places that divide us, both within ourselves and in our everyday relationships.

Attitudes of expansion and curiosity inform Jungian inquiry. Alongside rational thinking and direct ways of knowing, nonlinear ways of knowing, such as fantasies, images, daydreams and nocturnal dreams are encouraged and valued.

Therapeutic engagement with Jungian methods of inquiry are in the service of healing relational ruptures and emotional woundedness. This can include dream interpretation wherein personal images and associations are deemed valuable, and active imagination, which supports the spontaneous generation of personal clusters of related images and ideas. The activation of personal images can help facilitate conversations between the conscious and unconscious minds, contributing to integration of the shadow, Jung’s term for the unclaimed or rejected parts of ourselves.

In addition to their application in Jungian analysis, Jungian ideas further offer a framework for viewing and meeting life in its multitudes of complexity. Typology provides a useful roadmap for understanding different ways of communicating; how we relate can be as unique as our individual typology.

Jung recognized that the world is full of opposing forces; he taught that we can learn to notice when we are in the grips of tension between such opposites. Sometimes life requires that we hold the tension between opposing viewpoints and positions. Our individual struggles are also humanity’s struggles: we are each individuals AND we are not alone.